Strategies for Learning Salient Characters of Plant Families?

| Daisy family Temporal range: Campanian[ane]–recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Twelve species of Asteraceae from the subfamilies Asteroideae, Carduoideae and Cichorioideae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Guild: | Asterales |

| Family unit: | Asteraceae Bercht. & J.Presl[2] |

| Type genus | |

| Aster 50. | |

| Subfamilies[ commendation needed ] | |

| |

| Diversity[three] | |

| 1,911 genera | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

The family Daisy family (),[ citation needed ] alternatively Compositae (),[ citation needed ] consists of over 32,000 known species of flowering plants in over i,900 genera within the club Asterales. Commonly referred to every bit the aster, daisy, composite, or sunflower family unit, Compositae were kickoff described in the year 1740. The number of species in Asteraceae is rivaled only by the Orchidaceae, and which is the larger family is unclear as the quantity of extant species in each family is unknown.

Most species of Asteraceae are almanac, biennial, or perennial herbaceous plants, but there are likewise shrubs, vines, and copse. The family unit has a widespread distribution, from subpolar to tropical regions in a broad variety of habitats. Most occur in hot desert and common cold or hot semi-desert climates, and they are plant on every continent merely Antarctica. The chief common characteristic is the existence of sometimes hundreds of tiny individual florets which are held together by protective involucres in flower heads, or more technically, capitula.

The oldest known fossils are pollen grains from the Late Cretaceous (Campanian to Maastrichtian) of Antarctica, dated to c. 76–66 million years (myr). Information technology is estimated that the crown group of Aster family evolved at least 85.nine myr (Belatedly Cretaceous, Santonian) with a stalk node age of 88–89 myr (Tardily Cretaceous, Coniacian).

Asteraceae is an economically important family unit, providing food staples, garden plants, and herbal medicines. Species outside of their native ranges can be considered weedy or invasive.

Description [edit]

Members of the Asteraceae are mostly herbaceous plants, but some shrubs, vines, and trees (such as Lachanodes arborea) practise exist. Asteraceae species are generally easy to distinguish from other plants because of their unique inflorescence and other shared characteristics, such as the joined anthers of the stamens.[five] Even so, determining genera and species of some groups such as Hieracium is notoriously difficult (encounter "damned yellow composite" for example).[vi]

Roots [edit]

Members of the family Asteraceae generally produce taproots, but sometimes they possess gristly root systems. Some species take underground stems in the form of caudices or rhizomes. These can be fleshy or woody depending on the species.[7]

Stems [edit]

Stems are herbaceous, aerial, branched, and cylindrical with glandular hairs, generally erect, just can exist prostrate to ascending. The stems can contain secretory canals with resin,[7] or latex which is specially common among the Cichorioideae.[8]

Leaves [edit]

Leaves can be alternating, contrary, or whorled. They may be unproblematic, but are often deeply lobed or otherwise incised, often conduplicate or revolute. The margins besides tin exist entire or toothed. Resin[7] or latex[8] likewise can be present in the leaves.

Inflorescences [edit]

Nearly all Asteraceae carry their flowers in dense blossom heads called capitula. They are surrounded by involucral bracts, and when viewed from a distance, each capitulum may appear to exist a single flower. Enlarged outer (peripheral) flowers in the capitulum may resemble petals, and the involucral bracts may look similar a calyx.

Floral heads [edit]

A typical Asteraceae blossom head showing the individual flowers (Bidens torta)

A flower head showing the individual flowers opening from the outside (Argyranthemum 'Bridesmaid')

In plants of the family unit Compositae, what appears to be a single bloom is really a cluster of much smaller flowers. The overall appearance of the cluster, as a single flower, functions in attracting pollinators in the same way as the structure of an individual bloom in some other plant families. The older family unit name, Sunflower family, comes from the fact that what appears to be a single flower is actually a blended of smaller flowers.[nine]

The "petals" or "sunrays" in a sunflower caput are actually private strap-shaped[x] flowers chosen ray flowers, and the "sun disk" is made of smaller circular shaped individual flowers called disc flowers. The word "aster" means "star" in Greek, referring to the appearance of some family members, as a "star" surrounded past "rays". The cluster of flowers that may appear to exist a single flower, is called a caput. The entire caput may move tracking the sun, like a "smart" solar panel, which maximizes reflectivity of the whole unit and can thereby attract more than pollinators.[nine]

On the outside the flower heads are small bracts that wait like scales. These are chosen phyllaries, and together they grade the involucre that protects the private flowers in the head before they open.[ix] : 29 The individual heads take the smaller private flowers bundled on a round or dome-like construction chosen the receptacle. The flowers mature first at the outside, moving toward the eye, with the youngest in the middle.[nine]

The individual flowers in a caput have 5 fused petals (rarely iv), but instead of sepals, accept threadlike, hairy, or bristly structures singularly called a pappus, plural pappi, which environs the fruit and tin stick to creature fur or be lifted by wind, aiding in seed dispersal. The whitish fluffy head of a dandelion, usually diddled on by children, is made of pappi with tiny seeds attached at the ends. The pappi provide a parachute similar structure to help the seed exist carried away in the wind.[9]

A ray flower is a 3-tipped (3-lobed), strap-shaped, individual blossom in the head of some members of the family Asteraceae.[nine] [10] Sometimes a ray flower is two-tipped (two-lobed). The corolla of the ray blossom may have 2 tiny teeth opposite the three-lobed strap, or natural language, indicating evolution by fusion from an originally five-part corolla. Sometimes, the 3:2 arrangement is reversed, with 2 tips on the tongue, and 0 or 3 tiny teeth reverse the natural language. A ligulate flower is a 5-tipped, strap-shaped, individual flower in the heads of other members.[9] A ligule is the strap-shaped tongue of the corolla of either a ray flower or of a ligulate flower.[10] A deejay blossom (or disc flower) is a radially symmetric (i.e., with identical shaped petals arranged in circle around the center) individual blossom in the head, which is ringed by ray flowers when both are present.[9] [10] Sometimes ray flowers may be slightly off from radial symmetry, or weakly bilaterally symmetric, as in the case of desert pincushions Chaenactis fremontii.[ix]

A radiate head has disc flowers surrounded by ray flowers. A ligulate head has all ligulate flowers. When a sunflower family unit flower head has just disc flowers that are sterile, male person, or have both male person and female person parts, it is a discoid head. Disciform heads have only disc flowers, but may take two kinds (male flowers and female person flowers) in one head, or may take different heads of two kinds (all male, or all female). Pistillate heads accept all female flowers. Staminate heads have all male person flowers. Sometimes, simply rarely, the head contains just a unmarried blossom, or has a single flowered pistillate (female) head, and a multi-flowered male person staminate (male) head.[9]

Floral structures [edit]

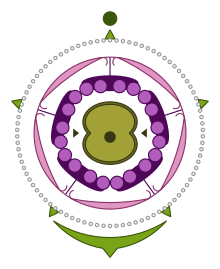

Blossom diagram of Carduus (Carduoideae) shows (outermost to innermost): subtending bract and stem centrality; calyx forming a pappus; fused corolla; stamens fused to corolla; gynoecium with two carpels and i locule

The distinguishing feature of Aster family is their inflorescence, a type of specialised, composite flower head or pseudanthium, technically called a calathium or capitulum,[11] [12] that may look superficially similar a single bloom. The capitulum is a contracted raceme composed of numerous individual sessile flowers, called florets, all sharing the same receptacle.

A prepare of bracts forms an involucre surrounding the base of the capitulum. These are called "phyllaries", or "involucral bracts". They may simulate the sepals of the pseudanthium. These are generally herbaceous simply tin also be brightly coloured (e.one thousand. Helichrysum) or have a scarious (dry and membranous) texture. The phyllaries tin can be gratis or fused, and arranged in 1 to many rows, overlapping like the tiles of a roof (imbricate) or not (this variation is of import in identification of tribes and genera).

Each floret may exist subtended past a bract, chosen a "palea" or "receptacular bract". These bracts are frequently called "crust". The presence or absence of these bracts, their distribution on the receptacle, and their size and shape are all important diagnostic characteristics for genera and tribes.

The florets have five petals fused at the base to form a corolla tube and they may be either actinomorphic or zygomorphic. Disc florets are usually actinomorphic, with five petal lips on the rim of the corolla tube. The petal lips may be either very short, or long, in which instance they form deeply lobed petals. The latter is the simply kind of floret in the Carduoideae, while the first kind is more widespread. Ray florets are always highly zygomorphic and are characterised by the presence of a ligule, a strap-shaped structure on the edge of the corolla tube consisting of fused petals. In the Asteroideae and other modest subfamilies these are ordinarily borne only on florets at the circumference of the capitulum and accept a 3+two scheme – above the fused corolla tube, 3 very long fused petals form the ligule, with the other two petals existence inconspicuously small. The Cichorioideae has just ray florets, with a 5+0 scheme – all 5 petals form the ligule. A four+1 scheme is found in the Barnadesioideae. The tip of the ligule is often divided into teeth, each one representing a petal. Some marginal florets may have no petals at all (filiform floret).

The calyx of the florets may be absent-minded, but when present is always modified into a pappus of 2 or more teeth, scales or bristles and this is often involved in the dispersion of the seeds. As with the bracts, the nature of the pappus is an important diagnostic characteristic.

At that place are usually five stamens. The filaments are fused to the corolla, while the anthers are generally connate (syngenesious anthers), thus forming a sort of tube around the manner (theca). They normally accept basal and/or upmost appendages. Pollen is released inside the tube and is collected around the growing style, and then, as the way elongates, is pushed out of the tube (nüdelspritze).

The pistil consists of 2 connate carpels. The style has two lobes. Stigmatic tissue may exist located in the interior surface or grade two lateral lines. The ovary is inferior and has just ane ovule, with basal placentation.

Fruits and seeds [edit]

In members of the Asteraceae the fruit is achene-like, and is chosen a cypsela (plural cypselae). Although there are two fused carpels, at that place is but one locule, and only 1 seed per fruit is formed. It may sometimes be winged or spiny considering the pappus, which is derived from calyx tissue oftentimes remains on the fruit (for example in dandelion). In some species, however, the pappus falls off (for instance in Helianthus). Cypsela morphology is often used to help decide establish relationships at the genus and species level.[13] The mature seeds usually have little endosperm or none.[5]

Pollen [edit]

The pollen of composites is typically echinolophate, a morphological term meaning "with elaborate systems of ridges and spines dispersed around and between the apertures."[14]

Metabolites [edit]

In Sunflower family, the energy shop is generally in the form of inulin rather than starch. They produce iso/chlorogenic acid, sesquiterpene lactones, pentacyclic triterpene alcohols, diverse alkaloids, acetylenes (cyclic, effluvious, with vinyl terminate groups), tannins. They take terpenoid essential oils which never contain iridoids.[fifteen]

Compositae produce secondary metabolites, such every bit flavonoids and terpenoids. Some of these molecules can inhibit protozoan parasites such as Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, Leishmania and parasitic abdominal worms, and thus have potential in medicine.[16]

Taxonomy [edit]

History [edit]

Compositae, the original name for Sunflower family, were first described in 1740 by Dutch botanist Adriaan van Royen.[17] : 117–118 Traditionally, two subfamilies were recognised: Asteroideae (or Tubuliflorae) and Cichorioideae (or Liguliflorae).[ commendation needed ] The latter has been shown to exist extensively paraphyletic, and has now been divided into 12 subfamilies, but the sometime still stands.[18] [ needs update ] The written report of this family is known equally synantherology.

Phylogeny [edit]

The phylogenetic tree presented beneath is based on Panero & Funk (2002)[18] updated in 2014,[19] and now too includes the monotypic Famatinanthoideae.[19] [20] [21] [ needs update ] The diamond (♦) denotes a very poorly supported node (<50% bootstrap support), the dot (•) a poorly supported node (<lxxx%).[fifteen]

The family includes over 32,000 currently accepted species, in over 1,900 genera (list) in 13 subfamilies.[3] [ needs update ] The number of species in the family Asteraceae is rivaled only by Orchidaceae.[fifteen] [22] Which is the larger family is unclear, because of the uncertainty about how many extant species each family includes.[ commendation needed ] The four subfamilies Asteroideae, Cichorioideae, Carduoideae and Mutisioideae incorporate 99% of the species diversity of the whole family unit (approximately 70%, 14%, 11% and iii% respectively).[ commendation needed ]

Because of the morphological complication exhibited past this family, like-minded on generic circumscriptions has often been hard for taxonomists. As a result, several of these genera have required multiple revisions.[5]

Paleontology and evolutionary processes [edit]

The oldest known fossils of members of Asteraceae are pollen grains from the Late Cretaceous of Antarctica, dated to ∼76–66 myr (Campanian to Maastrichtian) and assigned to the extant genus Dasyphyllum.[1] Barreda, et al. (2015) estimated that the crown group of Daisy family evolved at least 85.9 myr (Belatedly Cretaceous, Santonian) with a stem node age of 88–89 myr (Belatedly Cretaceous, Coniacian).[1]

It is not known whether the precise cause of their cracking success was the development of the highly specialised capitulum, their ability to store energy as fructans (mainly inulin), which is an advantage in relatively dry zones, or some combination of these and possibly other factors.[15] Heterocarpy, or the ability to produce different fruit morphs, has evolved and is common in Asteraceae. Information technology allows seeds to be dispersed over varying distances and each is adapted to different environments, increasing chances of survival.[23]

Etymology and pronunciation [edit]

The name Asteraceae () comes to international scientific vocabulary from New Latin, from Aster, the type genus, + -aceae,[24] a standardized suffix for establish family names in modern taxonomy. The genus proper name comes from the Classical Latin word aster, "star", which came from Ancient Greek ἀστήρ ( astḗr ), "star".[24] It refers to the star-similar form of the inflorescence.[ citation needed ]

The original name Compositae is still valid under the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants.[25] It refers to the "blended" nature of the capitula, which consist of a few or many individual flowers.[ citation needed ]

The vernacular name daisy, widely applied to members of this family unit, is derived from the Old English language name of the daisy (Bellis perennis): dæġes ēaġe, meaning "24-hour interval's middle". This is because the petals open up at dawn and close at dusk.[26]

Distribution and habitat [edit]

Compositae species have a widespread distribution, from subpolar to tropical regions in a wide variety of habitats. Most occur in hot desert and common cold or hot semi-desert climates, and they are found on every continent only Antarctica. They are especially numerous in tropical and subtropical regions (notably Central America, eastern Brazil, the Mediterranean, the Levant, southern Africa, central Asia, and southwestern China).[22] The largest proportion of the species occur in the arid and semi-arid regions of subtropical and lower temperate latitudes.[vii] The Asteraceae family comprises ten% of all flowering plant species.[27]

Ecology [edit]

Aster family are especially common in open and dry environments.[v] Many members of Asteraceae are pollinated by insects, which explains their value in attracting benign insects, but anemophily is also present (eastward.g. Ambrosia, Artemisia). There are many apomictic species in the family unit.

Seeds are usually dispersed intact with the fruiting body, the cypsela. Anemochory (current of air dispersal) is mutual, assisted by a hairy pappus. Epizoochory is another common method, in which the dispersal unit, a single cypsela (due east.g. Bidens) or entire capitulum (eastward.g. Arctium) has hooks, spines or some structure to attach to the fur or plumage (or even clothes, as in the photo) of an animal just to fall off later far from its mother institute.

Some members of Asteraceae are economically important as weeds. Notable in the U.s.a. are Senecio jacobaea (ragwort),[28] Senecio vulgaris (groundsel),[29] and Taraxacum (dandelion).[thirty] Some are invasive species in particular regions, often having been introduced by homo bureau. Examples include diverse tumbleweeds, Bidens, ragweeds, thistles, and dandelion.[31] Dandelion was introduced into North America past European settlers who used the young leaves as a salad greenish.[32]

Uses [edit]

Compositae is an economically important family, providing products such as cooking oils, foliage vegetables like lettuce, sunflower seeds, artichokes, sweetening agents, coffee substitutes and herbal teas. Several genera are of horticultural importance, including pot marigold (Calendula officinalis), Echinacea (coneflowers), diverse daisies, fleabane, chrysanthemums, dahlias, zinnias, and heleniums. Daisy family are important in herbal medicine, including Grindelia, yarrow, and many others.[35]

Commercially of import plants in Aster family include the food crops Lactuca sativa (lettuce), Cichorium (chicory), Cynara scolymus (earth artichoke), Helianthus annuus (sunflower), Smallanthus sonchifolius (yacón), Carthamus tinctorius (safflower) and Helianthus tuberosus (Jerusalem artichoke).[36]

Plants are used equally herbs and in herbal teas and other beverages. Chamomile, for example, comes from two different species: the annual Matricaria chamomilla (High german chamomile) and the perennial Chamaemelum nobile (Roman chamomile). Calendula (known every bit pot marigold) is grown commercially for herbal teas and potpourri. Echinacea is used as a medicinal tea. The wormwood genus Artemisia includes absinthe (A. absinthium) and tarragon (A. dracunculus). Winter tarragon (Tagetes lucida), is unremarkably grown and used as a tarragon substitute in climates where tarragon will not survive.[ commendation needed ]

Many members of the family unit are grown as ornamental plants for their flowers, and some are important ornamental crops for the cut flower industry. Some examples are Chrysanthemum, Gerbera, Calendula, Dendranthema, Argyranthemum, Dahlia, Tagetes, Zinnia, and many others.[37]

Many species of this family unit possess medicinal backdrop and are used as traditional antiparasitic medicine.[16]

Members of the family are also usually featured in medical and phytochemical journals because the sesquiterpene lactone compounds contained inside them are an important cause of allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy to these compounds is the leading cause of allergic contact dermatitis in florists in the United states of america.[39] Pollen from ragweed Ambrosia is amongst the primary causes of so-called hay fever in the Us.[40]

Aster family are likewise used for some industrial purposes. French Marigold (Tagetes patula) is common in commercial poultry feeds and its oil is extracted for uses in cola and the cigarette industry. The genera Chrysanthemum, Pulicaria, Tagetes, and Tanacetum contain species with useful insecticidal properties. Parthenium argentatum (guayule) is a source of hypoallergenic latex.[37]

Several members of the family are copious nectar producers[37] and are useful for evaluating pollinator populations during their bloom.[ commendation needed ] Centaurea (knapweed), Helianthus annuus (domestic sunflower), and some species of Solidago (goldenrod) are major "dear plants" for beekeepers. Solidago produces relatively loftier poly peptide pollen, which helps honey bees over winter.[41]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Barreda, Viviana D.; Palazzesi, Luis; Tellería, Maria C.; Olivero, Eduardo B.; Raine, J. Ian; Wood, Félix (2015). "Early on development of the angiosperm clade Asteraceae in the Cretaceous of Antarctica". Proceedings of the National University of Sciences of the U.s.. 112 (35): 10989–10994. Bibcode:2015PNAS..11210989B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1423653112. PMC4568267. PMID 26261324.

- ^ "Asteraceae Bercht. & J.Presl". Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved fourteen July 2017.

- ^ a b "The Institute List: Sunflower family". The Plant List (www.theplantlist.org). Majestic Botanic Gardens Kew and Missouri Botanic Garden. 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ^ "Family: Asteraceae Bercht. & J. Presl, nom. cons". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN) (www.ars-grin.gov). Beltsville, Maryland: USDA, ARS, National Genetic Resources Plan, National Germplasm Resource Laboratory. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 12 June 2008.

- ^ a b c d Judd, W.S.; Campbell, C.Southward.; Kellogg, E.A.; Stevens, P.F.; Donaghue, M.J. (2007). Constitute Systematics: A Phylogenetic Approach (3rd ed.). Sunderland: Sinauer Associates. ISBN978-0878934072.

- ^ Mandel, Jennifer R.; Dikow, Rebecca B.; Siniscalchi, Carolina G.; Thapa, Ramhari; Watson, Linda E.; Funk, Vicki A. (ix July 2019). "A fully resolved backbone phylogeny reveals numerous dispersals and explosive diversifications throughout the history of Asteraceae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (28): 14083–14088. doi:10.1073/pnas.1903871116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC6628808. PMID 31209018.

- ^ a b c d Barkley, Theodore M.; Brouillet, Luc; Strother, John L. (half dozen Nov 2020). "Daisy family Berchtold & J. Presl - Composite Family". Flora of North America (floranorthamerica.org) . Retrieved eighteen February 2021.

- ^ a b Kilian, Norbert; Gemeinholzer, Birgit; Lack, Hans Walter. "24. Cichorieae" (PDF). In Funk, V.A.; Susanna, A.; Stuessy, T.E.; Bayer, R.J. (eds.). Systematics, evolution and biogeography of Compositae. Vienna: International Association for Found Taxonomy. Retrieved 20 Feb 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f one thousand h i j Morhardt, Sia; Morhardt, Emil (2004). California desert flowers: an introductions to families, genera, and species. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Printing. pp. 29–32. ISBN978-0520240032.

- ^ a b c d MacKay, Pam (2013). Mojave Desert Wildflowers: A Field Guide To Wildflowers, Trees, And Shrubs Of The Mojave Desert, Including The Mojave National Preserve, Death Valley National Park, and Joshua Tree National Park (Wildflower Series). Guilford, Connecticut: FalconGuides. p. 35 (effigy 5). ISBN978-0762780334.

- ^ Beentje, Henk (2010). The Kew Plant Glossary, an illustrated dictionary of plant terms. Richmond, U.1000.: Kew Publishing. ISBN978-1842464229.

- ^ Conductor, G. (1966). A Dictionary of Botany, including terms used in biochemistry, soil science, and statistics. Lawman and Visitor Ltd. ISBN0094504903. OCLC 959412625.

- ^ McKenzie, R.J.; Samuel, J.; Muller, East.Thou.; Skinner, A.One thousand.W.; Barker, Due north.P. (2005). "Morphology of cypselae in subtribe Arctotidinae (Compositae–Arctotideae) and its taxonomic implications". Register of the Missouri Botanical Garden. 92 (four): 569–594. JSTOR 40035740. Retrieved 18 February 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Tomb, A. Spencer (May–June 1974). "Pollen morphology and detailed construction of family Asteraceae, tribe Cichorieae. I. Subtribe Stephanomeriinae". American Journal of Phytology. 61 (5): 486–498. doi:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1974.tb10788.x. JSTOR 2442020.

- ^ a b c d Stevens, Peter F. (2001). "Angiosperm Phylogeny Website: Asterales". Angiosperm Phylogeny Website.

- ^ a b Panda, Sujogya Kumar; Luyten, Walter (2018). "Antiparasitic activity in Sunflower family with special attending to ethnobotanical employ by the tribes of Odisha, Bharat". Parasite. 25: ten. doi:10.1051/parasite/2018008. ISSN 1776-1042. PMC5847338. PMID 29528842.

- ^ von Royen, Adriani (1740). Florae leydensis prodromus : exhibens plantas quae in Horto academico Lugduno-Batavo aluntur (in Latin). Lugduni Batavorum [Leiden]: Apud Samuelen Luchtmans academiae typographum. Retrieved xviii Feb 2021 – via Botanicus.

- ^ a b Panero, J.Fifty.; Funk, 5.A. (2002). "Toward a phylogenetic subfamilial nomenclature for the Sunflower family (Asteraceae)". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 115: 909–922 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- ^ a b Panéro, José 50.; Freire, Susana East.; Ariza Espinar, Luis; Crozier, Bonnie S.; Barboza, Gloria Eastward.; Cantero, Juan J. (2014). "Resolution of deep nodes yields an improved backbone phylogeny and a new basal lineage to report early development of Asteraceae". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 80 (1): 43–53. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2014.07.012. PMID 25083940 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Fu, Zhi-Xi; Jiao, Bo-Han; Nie, Bao; Zhang, Guo-Jin; Gao, Tian-Gang (22 July 2016). "A comprehensive generic‐level phylogeny of the sunflower family: Implications for the systematics of Chinese Aster family". Journal of Systematics and Evolution. 54 (iv): 416–437. doi:10.1111/jse.12216. S2CID 89115861 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Funk, Vicki A.; Fragman-Sapir, Ori (2009). "22. Gymnarrheneae (Gymnarrhenoideae)" (PDF). In V.A. Funk; A. Susanna; T. Stuessy; R. Bayer (eds.). Systematics, Evolution, and Biogeography of Compositae. Vienna: International Clan for Plant Taxonomy. pp. 327–332. ISBN978-3950175431.

- ^ a b Panero, Jose L.; Crozier, Bonnie Due south. (27 Jan 2012). "Daisy family. Sunflowers, daisies". The Tree of Life Web Projection (tolweb.org).

- ^ Gardocki, Mary E.; Zablocki, Heather; El-Keblawy, Ali; Freeman, D. Carl (2000). "Heterocarpy in Calendula micrantha (Asteraceae): the effects of competition and availability of water on the performance of offspring from dissimilar fruit morphs". Evolutionary Environmental Research. 2 (vi): 701–718. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster'southward Unabridged Dictionary, Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "International Code of Classification for algae, fungi, and plants – Article 18.v". iapt-taxon.org.

- ^ "daisy, n.". OED Online. Oxford Academy Printing. March 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ Mandel, Jennifer R.; Dikow, Rebecca B.; Siniscalchi, Carolina M.; Thapa, Ramhari; Watson, Linda E.; Funk, Vicki A. (ix July 2019). "A fully resolved courage phylogeny reveals numerous dispersals and explosive diversifications throughout the history of Asteraceae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (28): 14083–14088. doi:10.1073/pnas.1903871116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC6628808. PMID 31209018.

- ^ "Tansy ragwort". Washington State Noxious Weed Control Board (www.nwcb.wa.gov) . Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Common groundsel". Washington Country Noxious Weed Control Lath (www.nwcb.wa.gov) . Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ González-Castejón, Marta; Visioli, Francesco; Rodriguez-Casado, Arantxa (17 August 2012). "Diverse biological activities of dandelion". Diet Reviews. 70 (nine): 534–547. doi:ten.1111/j.1753-4887.2012.00509.x. ISSN 0029-6643. PMID 22946853.

- ^ Martín-Forés, Irene; Acosta-Gallo, Belén; Castro, Isabel; de Miguel, José M.; del Pozo, Alejandro; Casado, Miguel A. (xiv June 2018). "The invasiveness of Hypochaeris glabra (Asteraceae): Responses in morphological and reproductive traits for exotic populations". PLoS 1. xiii (6): e0198849. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198849. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC6002075. PMID 29902275.

- ^ "Taraxacum officinale: dandelion". Invasive Plant Atlas of the Us (www.invasiveplantatlas.org) . Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- ^ "Senecio angulatus (Cape ivy, Climbing groundsel, Creeping groundsel)". AUB Mural Institute Database (landscapeplants.aub.edu.lb). Beirut, Lebanon: American Academy of Beirut. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Senecio angulatus - climbing groundsel". Brisbane City Council weed identification tool (weeds.brisbane.qld.gov.au). Brisbane, Queensland, Australia: Brisbane City Quango. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Michel, Jennifer; Abd Rani, Nur Zahirah; Husain, Khairana (2020). "A Review on the Potential Use of Medicinal Plants From Asteraceae and Lamiaceae Establish Family in Cardiovascular Diseases". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 11: 852. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00852. ISSN 1663-9812. PMC7291392. PMID 32581807.

- ^ "Asteraceae: The sunflower family" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Singh, Rajendra; Singh, Garima; Tiwari, Ajeet; Patel, Shveta; Agrawal, Ruhi; Sharma, Akhilesh; Singh, B. (2015). "Diversity of host plants of aphids (Homoptera: Aphididae) infesting Asteraceae in Republic of india". International Journal of Zoological Investigations. 1 (2): 137–167. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Auld, B.A.; Meld, R.West. (1992). Weeds: an illustrated botanical guide to the weeds of Australia. Melbourne: Inkata Press. p. 264. ISBN978-0909605377.

- ^ Odom, R.B.; James, Westward.D.; Berger, T.G. (2000). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. Westward.B. Saunders Company. p. 1135. ISBN978-0721658322.

- ^ Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. "Ragweed Allergy". Archived from the original on seven October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- ^ "Five Plants to Help Pollinators". The Xerces Society. 2016. Retrieved ii June 2020.

Goldenrods are among the about important tardily-season pollinator plants.

Bibliography [edit]

- Funk, Vicki A.; Susanna, A.; Stuessy, T. F.; Bayer, R. J., eds. (2009). Systematics, Evolution, and Biogeography of Asteraceae. Vienna: International Association for Establish Taxonomy. ISBN978-3-9501754-three-1. (Available here at Internet Archive)

External links [edit]

- Aster family at the Angiosperm Phylogeny Website

- Compositae.org – Compositae Working Group (CWG) and Global Compositae Database (GCD)

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Asteraceae

0 Response to "Strategies for Learning Salient Characters of Plant Families?"

Postar um comentário